Dada Breton by Matthew S. Witkovsky p127

October Vol. 105, Dada (Summer, 2003)

Claire Bishop takes the title of her book Artificial Hells from Andre Breton, founder of surrealism, writing on that period.

While Grant Kester in ‘Autonomy, Antagonism and the Aesthetic’ champions participatory work, including work made with a moral intent and ‘within a tradition of cultural rebellion’, Claire Bishop seems to believe that the aesthetic qualities of art suffers when it takes on social, ethical concerns.

Through the history of theatre and performance, the book draws out a history of visual art, claiming that participatory art, while most popular since the 1990s, can be traced back throughout the twentieth century.

In a talk at Kaaitheater (Brussels) in 2013, Claire Bishop says that the American term ‘social practice’ is telling, as it removes art from the equation. (But you could equally argue that about Duchamp’s readymades.)

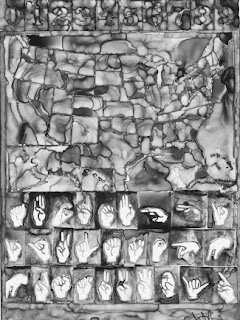

Dr Toby Lowe of Newcastle University/Helix Arts created this table to make the respective positions of the two writers clear.

Claire Bishop asserts that the good intentions of the participatory art cannot make up for a loss of aesthetic quality.

But I don’t think it’s necessarily true that there has to be loss of aesthetic quality.

Three inspiring artists in my field make art in this way. To me, the aesthetic quality of their work is still high, whilst they also engage with social issues and include other people in its creation.

The Henningham Family Press’ work is based on printmaking, book arts and publishing, and often includes performance outside a gallery setting (eg during the London Word Festival in 2010 they set up a screenprinting ‘Chip Shop’ in the Red Art Café in Dalston)

|

| Henningham Family Press at the London Word Festival, 2010 |

I wrote in detail on Gallery Ell about the Henningham Family Press and their day of participatory art based on George Orwell’s Maximum Wage in a church hall in Dalston (2015).

‘The Maximum Wage’ is a live art show about income inequality… inspired by George Orwell’s idea of a limitation of incomes in his essay ‘The Lion and the Unicorn’.

...The centrepiece is ‘The Maximum Wage’ screen-print production line, where the public will help print ‘Orwells’ – money that can be used at the event, as well as in several Hackney businesses. Each player’s ‘wages’ will be determined by their randomly allocated status and a spin of the wheel of fortune. Earnings will be capped at Orwell’s 10:1 or Osborne’s 330:1. It is the battle of the Georges.'

My interview with David Henningham, Gallery Ell March 2015

|

| Henningham Family Press - Maximum Wage (2015) - photo Wei Xun |

|

| Printing money |

|

| a printed 'Orwell' bank note |

Their art work is playful, imaginative, collaborative, political, creative, performance based and participatory. But I don't believe it suffers from any lack of aesthetic value.

The other artist is Swoon.

When I lived in Hackney around 2005 and started to take photos of street art, I became disillusioned quickly as it seemed that much street art was used cynically as a way for creatives just to get gallery representation.

The work itself had no content, it was just that people knew that Banksy was successful and that street art was fashionable and could sell. (Banksy’s excellent satire ‘Exit Through The Gift Shop’ tells this story.)

Swoon (Caledonia Curry) was an exception to this. I find both her work and her ethos inspiring. (She started as a printmaker working in large scale linocuts inspired by Expressionism and Japanese woodcuts.)

|

| paper pasteup, Bethnal Green circa 2005 |

|

| Swoon, Shoreditch circa 2011 |

|

| Murmuration installation, Black Rat Projects 2011 |

|

| Murmuration installation, Black Rat Projects 2011 |

|

| Murmuration installation, Black Rat Projects 2011 |

|

| Murmuration installation, Black Rat Projects 2011 |

She was given a solo show early in her career by gallerist Jeffrey Deitch.

|

| Swoon, Deitch Projects 2005 |

Many artists would have been happy with commercial success, but Swoon used this to fund other projects involving communities.

For example, with other artists and activists, Swoon gatecrashed the 2008 Venice Biennale, by sailing two giant rafts made from recycled rubbish through Europe to Venice, holding events and projects with audiences at stop off points along the way.

|

| Deitch 'Swimming Cities' 2008 photo by Tod Seelie |

|

| Deitch 'Swimming Cities' 2008 photo by Tod Seelie |

Other examples of Swoon's work include Konbit Shelter, a creative project to make sustainable, earthquake-proof buildings including a community centre and homes in Haiti, and the Transformazium – a collective of artists in recession-hit Braddock, Pennsylvania who work with residents on the creative use of the town’s derelict spaces.

I don’t believe that you have to choose between aesthetics and activism, Swoon is a shining example of someone who makes high quality work in aesthetic terms, while working with audiences to make participatory art.

I think that the key issue in these texts is access and entitlement.

Claire Bishop is an art historian with a degree from Cambridge University, and I would guess has never been anxious about entering an art gallery or museum.

But when I volunteered on a local advisory committee in 2006 for the exhibitions strategy at the V&A Museum of Childhood (probably the least intimidating, friendliest gallery/museum in London) Stephen Nicholls the Exhibition Manager said the biggest problem they faced was getting local people through the door in the first place.

They held English classes, playgroups and coffee mornings for people, just to get them used to entering the museum and feeling comfortable there – feeling that they were allowed into the place.

These articles made me consider who art belongs to. Taking art out of the museum and gallery and involving audiences in its making, opens it up for more people.

The art that Grant Kester writes about blurs the lines between the artist and the audience, and this is something that seems to make Claire Bishop cross. If art belongs to everyone and everyone has the ability to make art, it undermines the role of a critic, whose job is to judge what is pure or real or authentic art, and to be a kind of gatekeeper.

I found this week’s reading à propos as I’d just seen on Twitter a story about the V&A buying a part of ‘a nationally important and internationally recognised work of Brutalist architecture’, Robin Hood Gardens, a working class estate which has been demolished, so that the residents have lost their homes, to make way for ‘luxury flats’- ie property investment.

It was not deemed so important when they asked the curator to sign a petition to save their homes.

Stephen Pritchard,( co-founder of Artists Against Artwashing and PhD researcher at Northumbria University focusing on activist art) writes more about this and about artwashing here.

This story made me think about the role of art and how much more is at stake than just an argument between art critics.

Neither article specifically addresses art washing but this is a further twist in the story of how art functions in society.

References

Bishop, C. (2012) ‘The Social Turn: Collaboration and Its Discontents’ in Artificial Hells. London: Verso, pp. 11-40

Henningham Family Press 2015 https://maximumwage.uk/tag/henningham-family-press/

Kester, G. (2011) ‘Autonomy, Antagonism and the Aesthetic’ in The One and the Many: Contemporary Collaborative Art in a Global Context . Durham NC: Duke UP, pp.19-65

Lowe, T (2011) http://helixarts.blogspot.co.uk/2011/06/what-does-participatory-arts-mean.html

Pritchard, S (2017) http://colouringinculture.org/blog/artwashingrobinhoodgardens

Witkovsky, M.S. ( Summer 2003) Dada Breton p127 October Vol. 105, Dada